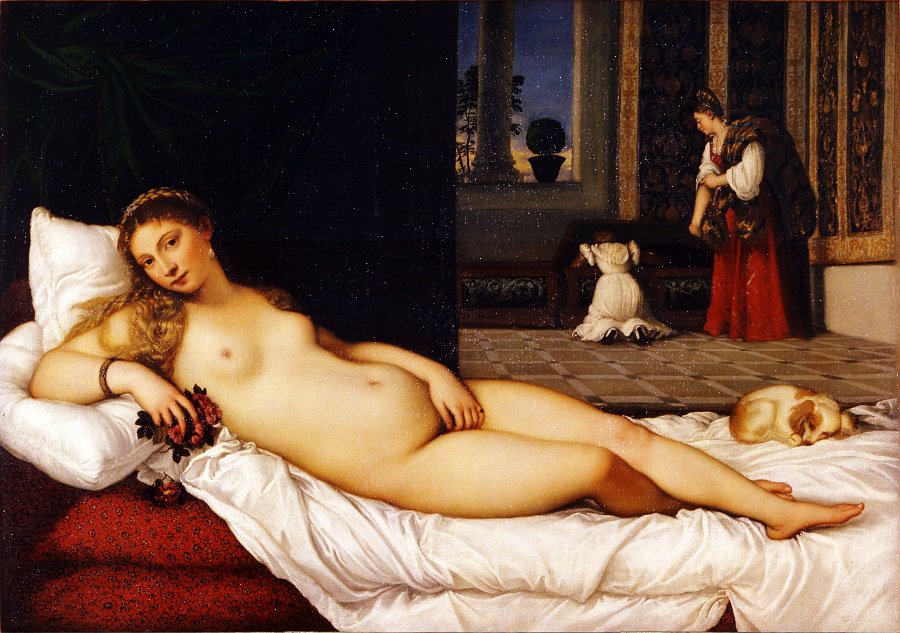

One of the best-known paintings of the Italian Renaissance, Titian's Venus of Urbino (1538) is a touchstone for the ideas and questions behind the Renaissance Skin project. Seduction and eroticism, love and beauty, marriage and fidelity are all themes to be found in Titian's painting. The role of skin in conjuring eroticism, fertility, and femininity may seem obvious; the role of skin in determining the relationship between these themes and more practical issues of marriage, domesticity, and household order less so. But Venus of Urbino brings these ideas together in a number of practical and material interventions.

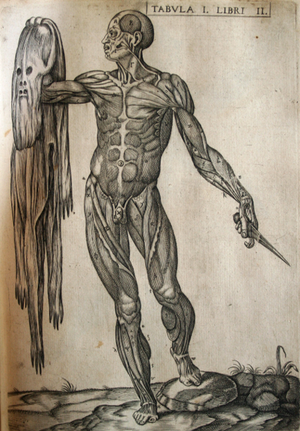

Skin has always been central to ideas about beauty. This was true not just in the many recipes for smoothing out complexions or those for hiding or curing freckles and blemishes, but also in the lengthy and detailed attention paid by the new artistic manuals of the Renaissance to representing it in paint. The art historian Mechthild Fend has recently shown how changes in colour, technique, and technologies facilitated and shaped medical attitudes to skin. Going forward, we will be asking questions about how aesthetic ideas of beauty, complexion, and the surface interacted with medical ideas about complexions, pores, and skin ailments.

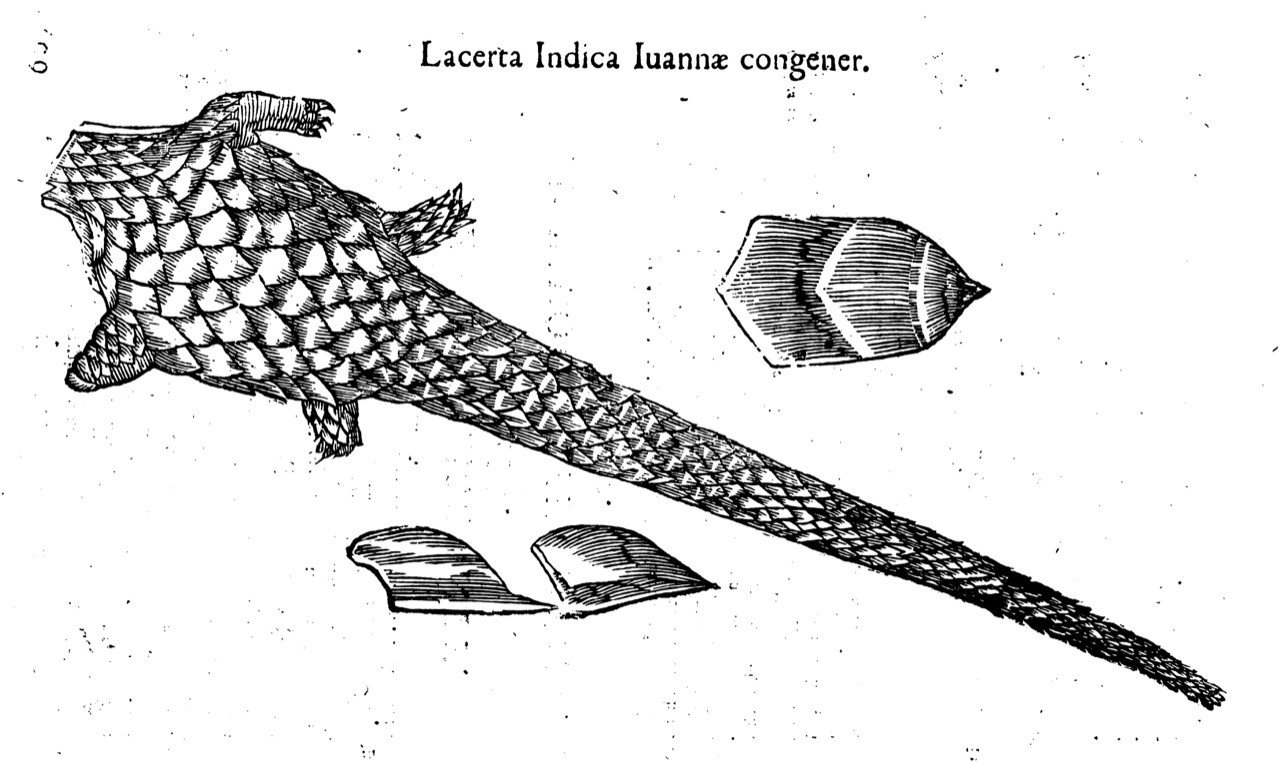

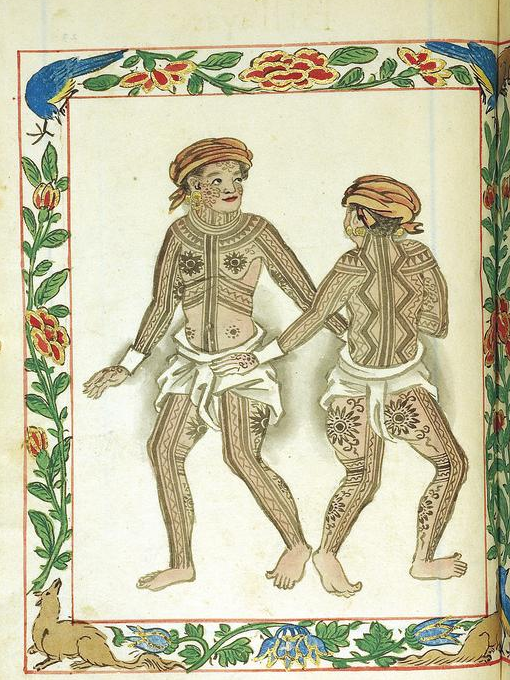

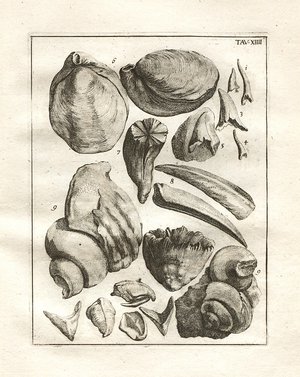

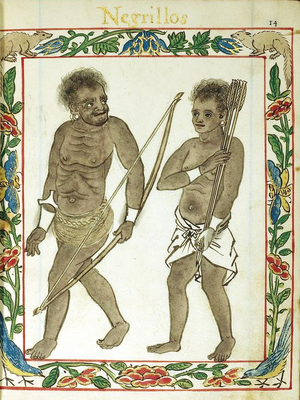

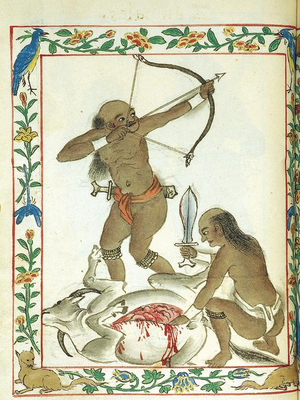

Crucially, this painting is not just about human skin but about animal skin too. Of particular note are the two serving women in the background packing (or unpacking) the large chest (cassone). The woman standing has a fur garment draped over her left shoulder. Titian painted the same model [as Venus] with a similar fur in the contemporary painting Girl in a Fur (1536-1538). His preoccupation with representing the luxurious skin of an animal against the naked skin of a woman throws up the division between human and animal. Unlike cultural (and theological) assumptions about the differences between humans and animals, Renaissance medical theory made no such distinction. A key concern then is how Renaissance anatomists conceptualised fur, feathers, and other sorts of animal skin. Did they think of it (like hair) as a kind of bodily excrement? Indeed, did they think of it at all?

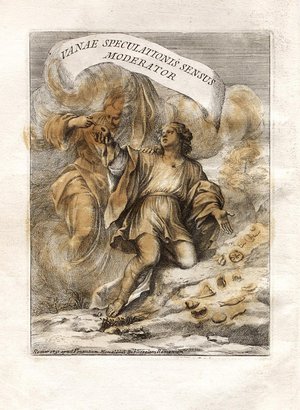

In some ways then, this is a painting that calls to mind the deepest questions about the relationship between surface and reality, and the way in which meaning is conveyed by matter. It is not just fur that Titian lingers on; the Venus of Urbino is a veritable encyclopedia of the textiles and textures of Renaissance materials - from the plush, draped velvets behind the reclining nude, her braided hair (a commonplace display of artistic virtuosity), to the silky fur of the small dog, curled at her feet. There is no doubt that the painting's meaning is enigmatic but this is precisely the point, for the tension between what skin reveals and what it conceals is one of the most prevalent aspects of its cultural representation. It is for this reason that skin is so often tied to the individual, not just in art, but also in literature, poetry, drama, metaphor, and idiom. The central thesis of our project is that the relationship between skin and the cultural idea of the human and non-human individual has a history - when we uncover it, what will we find?

HM

Image: Titian, The Venus of Urbino, 1538, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence