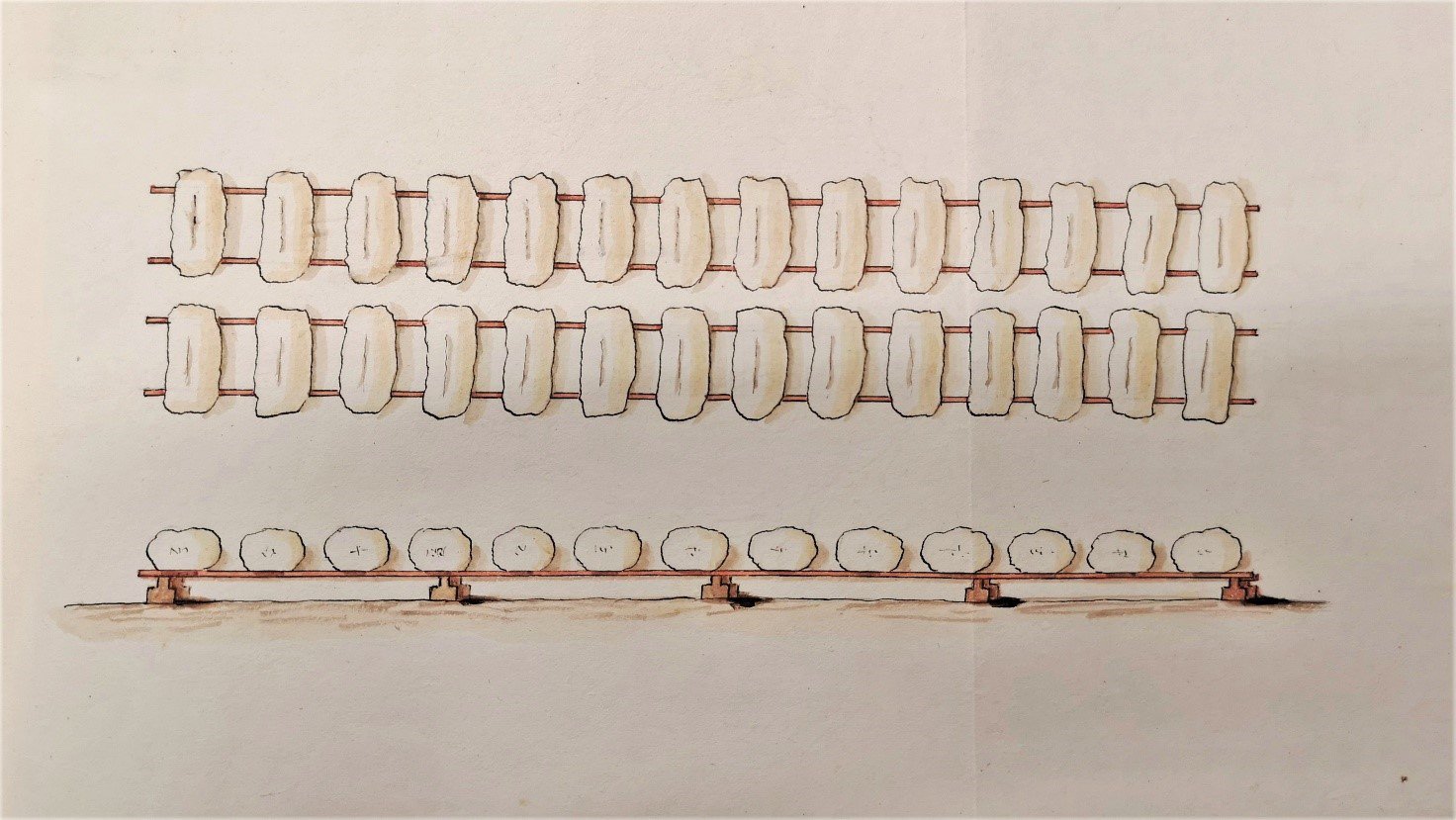

This drawing by the Dutch and Flemish artist Pieter Bruegel (1526/30-1569) shows a scene set in a bucolic landscape of an activity of which we are all aware but perhaps have given little consideration to – beekeeping. The theme of protecting skin is conjured up so vividly in this image and the work of a beekeeper would be virtually impossible without the head to toe coverings that he needed to apply. Although the beekeepers have made concerted effort to protect their skin, there are parts of their bodies that remain vulnerable. The cuffs of their sleeves are open (and not tied tight) and their hands are not covered, while there is limited protection to their legs and feet.

This drawing is rather enigmatic and this is due to the feeling of disquiet from not being able to see the faces of the three figures, who each wears a long coat with a hood and masks of basket-work to cover their face, as they work with the hives in the field. The meaning of the boy in the tree to the right of the image is unclear, the positioning of the hive lying on its side in the foreground suggests disruption, while the three figures themselves do seem furtive – the one on the right appears to struggle in his attempt to open the hive, the man to the left seems to be in the midst of a theft, while the stance of the central figure seems imposing.

Honey is (and was) an important commodity, used for food, medicines, and cosmetics, while beeswax could be used for candles (though mostly in churches and the homes of the wealthy) and to seal documents. Honey was used in the diet until the sixteenth century, when the availability of sugar grew. While the meaning behind this drawing remains unknown, many of Bruegel’s works do portray daily life and are set in Dutch towns and cities. Indeed, this image reflects quite accurately contemporary practices of beekeeping. For example, to the right we see a hive placed on pedestals to keep it clear of the ground and behind this is a wall or fence with an awning to protect it (and the other hives) from the wind.

There is a close copy of this drawing with the British Museum’s collections (SL,5236.59).

NAD

Image: Pieter Bruegel, The Beekeeper and the Birdnester, c.1568, Kupferstichkabinett inv. no. KdZ 713. © Foto: Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz. Fotograf/in: Jörg P. Anders