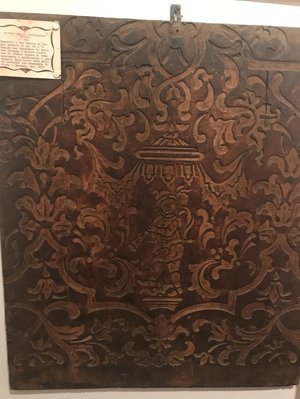

This panel of an animal skin is 26.6 cm x 26.6 cm. It was embroidered by either Mary, Queen of Scots, or Elizabeth Talbot, Countess of Shrewsbury, using a linen canvas with silk threads between 1570 and 1585. The animal is named incorrectly by the V&A as a civet cat; it is rather the skin of a common genet (Genetta genetta).

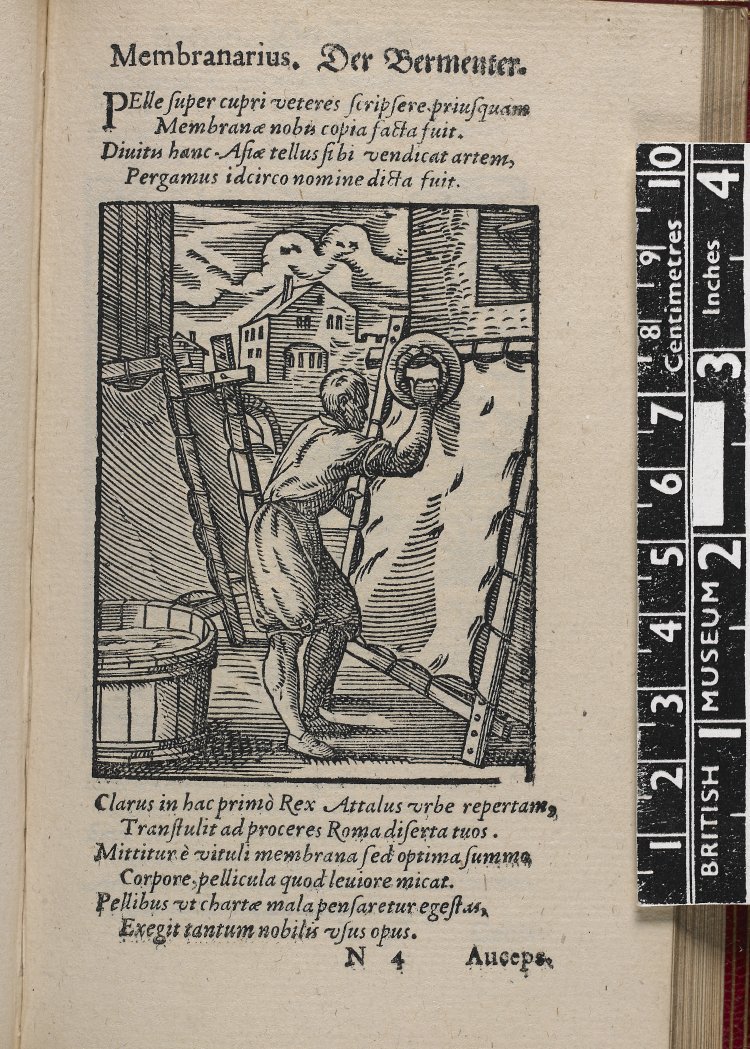

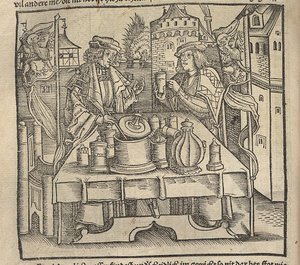

The animal can be identified by an inscription to the surface of the object, which reads ‘A GENE SKYN’. The image seems to be based on the woodcut of a genet’s skin that appears in the monumental Historia animalium (Book I De quadrupedibus viviparis, Zurich, 1551) and in the abbreviated Icones animalium (1553), works by the Swiss physician and natural philosopher Conrad Gessner. For Gessner, genets had the nature of a cat and a shape resembling a weasel. He cites Gerolamo Cardano (1501-1576), regarding the genet as having ‘more noble’ fur (along with the lynx) and that this fur was black and ash-coloured, with many distinct spots.

Gessner noted that he himself had seen had seen the skin of a genet,

which was, from the head to the top of the tail, the length four dodrans (3/4 of a

foot) and one palm, with the tail being two dodrans. He could see eight black

circles on this particular specimen’s tail, along with white and grey patches. It was

possible to discern ‘very elegant’ black spots all over the body. Gessner also remarked on the very good smell of the skin, which smelled like musk. Considering

its size, the spots, and its nature, Gessner judged the animal to be a kind of

small panther.

The skins were imported from Spain via Lyons and used for precious garments, imbued with an agreeable scent. Mary, Queen of Scots, also used Gessner woodcuts as the model for another embroidery of an animal, that of a cat (‘A catte’, Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 28224).

KWM

Further Reading:

- Conrad Gesner, Historia animalium: De

quadrupedibus viviparis (Zurich, 1551)

- Conrad Gesner, Icones animalium

(Zurich, 1553)

- Margaret Swain, The Needlework of Mary

Queen of Scots (Carlton, 1973)

Image © Victoria and Albert Museum, London (museum no. T.33FF-1955)