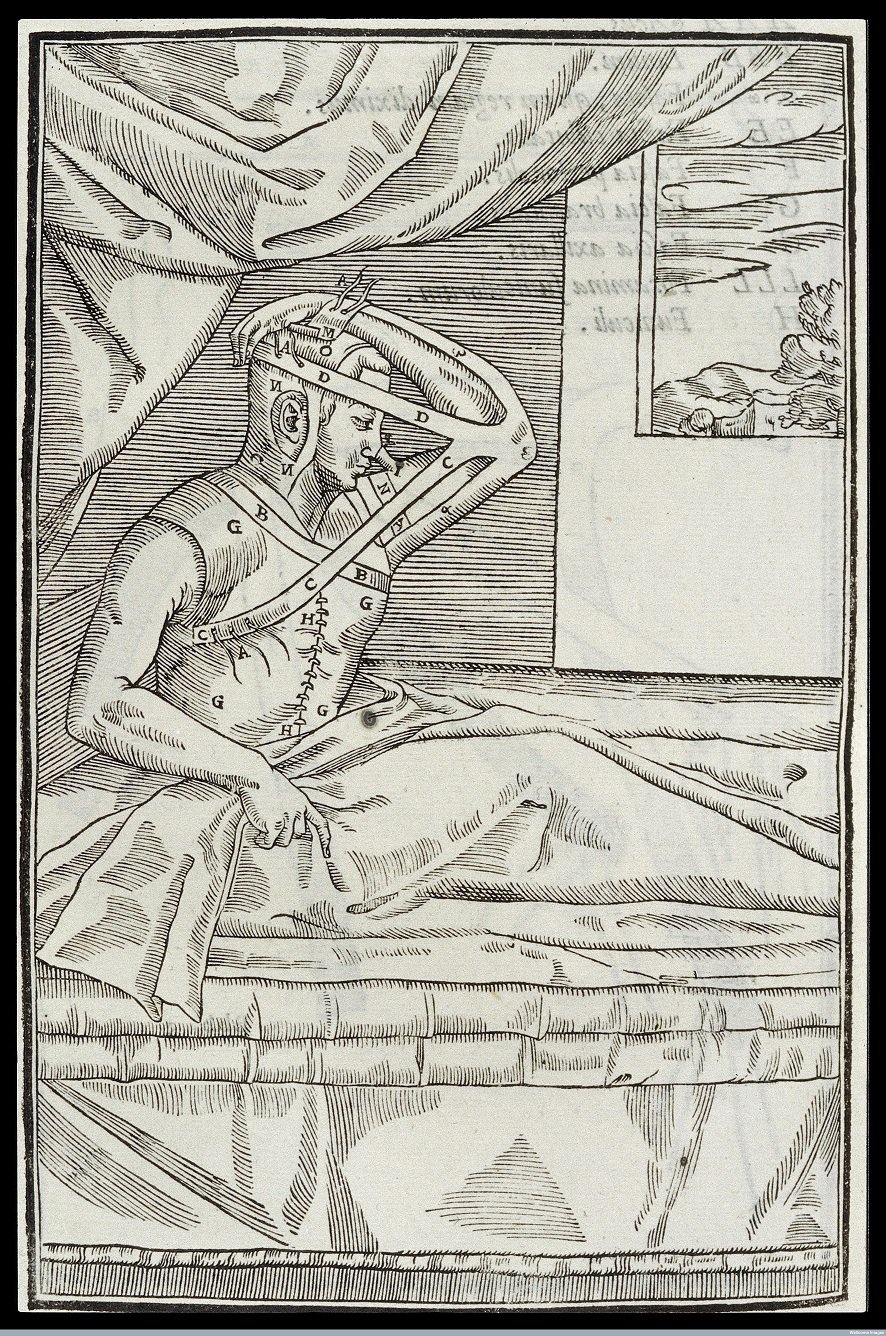

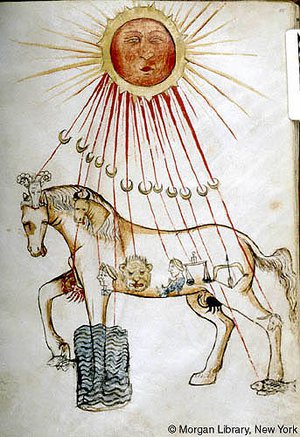

'Naturalists say that the inventor of phlebotomy was the hippo, an animal that lives on the Nile river, as big as a Frisian horse, of both earthly and aquatic nature; when it feels heavy for the excessive quantity of blood in its body, it goes into a reed bed or a similar place and under the push of a natural instinct he cuts its veins and lets blood out until it feels better. Then the hippo finds out some mud and patches up its wounds'. Taken from the Italian surgeon Tarduccio Salvi da Macerata’s bloodletting manual, which was first published in 1613, the 1650 edition of the book is accompanied by this eloquent illustration (Il ministro del medico, Rome, 1650, p. 4).

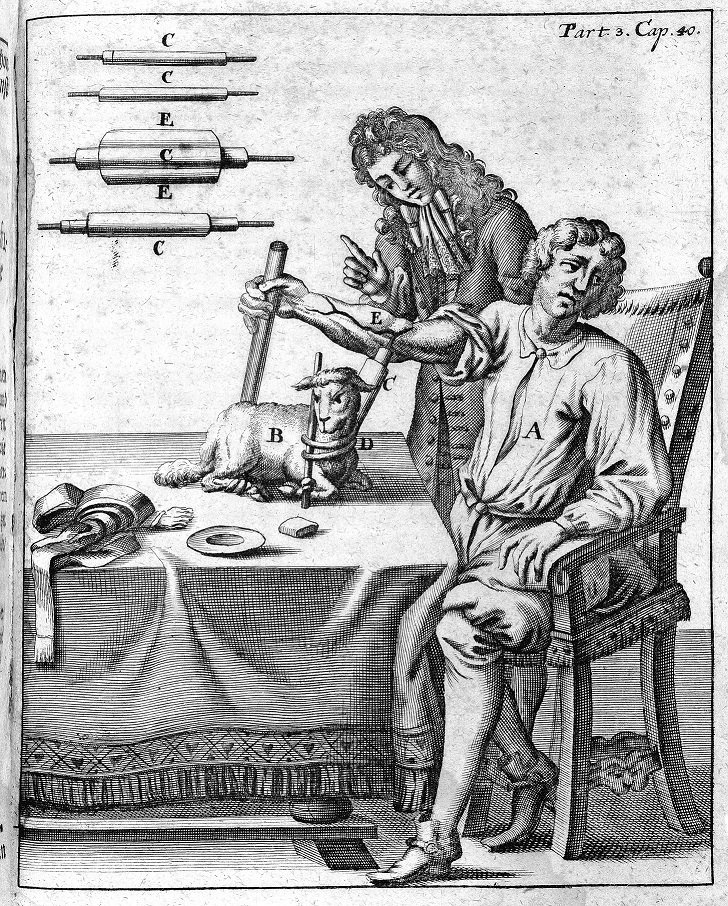

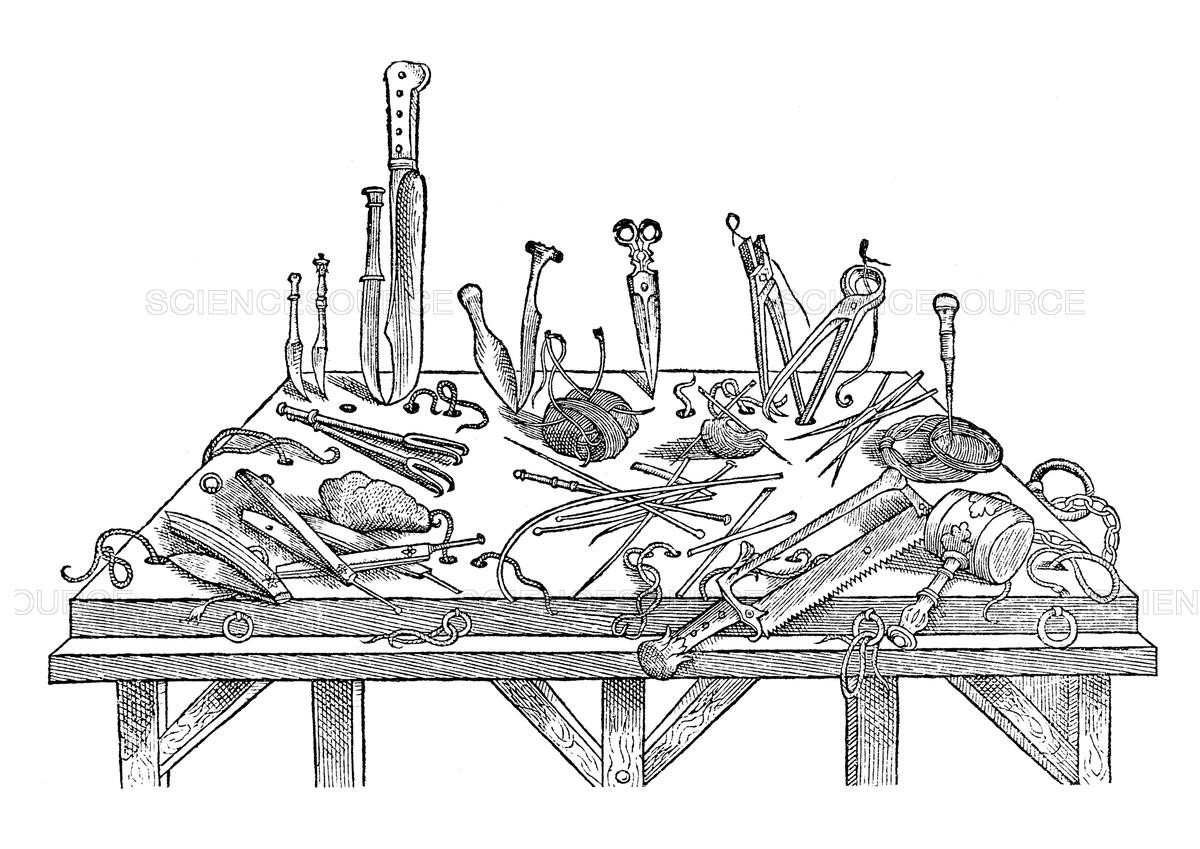

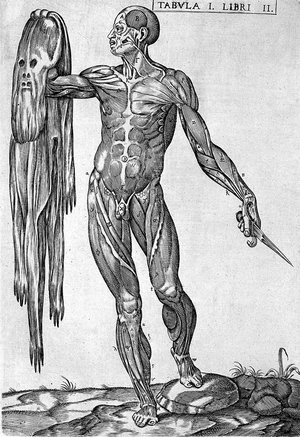

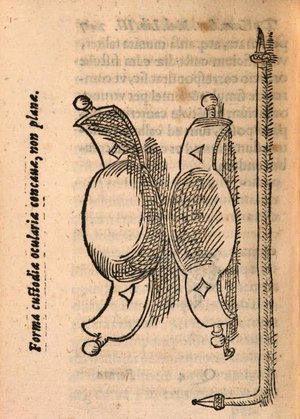

Bloodletting was the most common form of both preventative and therapeutic medical intervention in Renaissance Europe. It consisted of cutting one of the patient's vein to encourage noxious humours to move towards the open vein so that they could be expelled through the blood. It was performed with lancets, cupping glasses, or leeches and was meant to cover a range of treatments, including: healing fevers and pains; releasing bad humours from the whole body, particularly from the stomach; and even calming down the nerves.

But bloodletting had both a learned and a practical/technical pedigree. All classical Greek and Arabic authorities, including Hippocrates, Galen, and Ibn-Sina (Avicenna) had written about it, and it remained the subject of learned treatises throughout the early modern period. However, by the late middle ages its practice was entrusted to barbers and empirically-trained surgeons. The learned physician reserved for himself the role of supervisor.

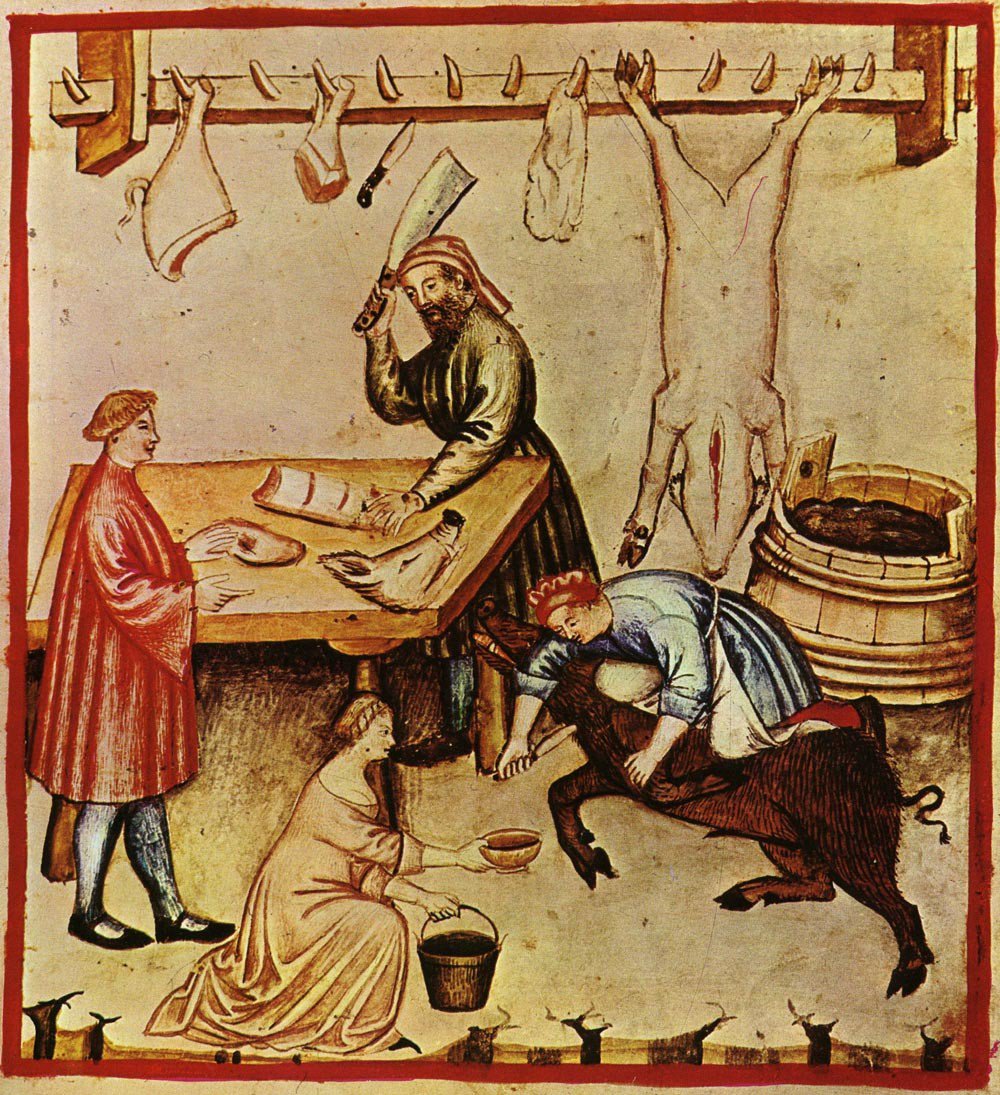

As a side effect of this, by the second half of the 16th century barber-surgeons began to write books about their trade. Along with an abundance of technical details about how to skilfully use their hands and tools, they also began to take pride in their profession, underlining its important history and its reliance upon the fundamental self-healing power of nature. Salvi’s story on the hippopotamus in fact originally comes from Pliny’s Natural History (VIII.96): ‘The hippopotamus stands out as an actual master in one department of medicine; for when its unceasing voracity has caused it to overeat itself it comes ashore to reconnoitre places where rushes have recently been cut, and where it sees an extremely sharp stalk it squeezes its body down on to it and makes a wound in a certain vein in its leg, and by thus letting blood unburdens its body, which would otherwise be liable to disease, and plasters up the wound again with mud’.

Barber-surgeons’ manuals are often marked by a strong naturalism. In this spirit, they often described the origins of phlebotomy through the observation of animal behaviour. The hippopotamus was chosen to be the exemplum. This emphasis on the fundamental continuity of humans, plants, and animals was also typical of Renaissance naturalism.

PS

Further Reading:

- Pedro Gil-Sotres, 'Derivation and Revulsion: The Theory and Practice of Medieval Phlebotomy' in Luis García Ballester (ed.), Practical Medicine from Salerno to the Black Death (Cambridge, 1994), pp.110-55

- Sachiko

Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature: Image, Text, and Argument in

Sixteenth-Century Human Anatomy and Medical Botany (Chicago, 2012)