On 15 February 2018, Natasha visited the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia and was treated to a behind-the-scenes exploration of this intriguing museum and its collections.

Appropriately, the strapline for Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum is ‘Disturbingly Informed’ and I cannot think of a more suitable term to sum up a visit to this museum. Opened on its original site in 1863, thanks to the founding collection of the American surgeon Thomas Dent Mutter (1811-59) – the umlaut was adopted after a trip to Europe to make him sound more European, the museum has an impressive (if somewhat graphic) collection of anatomical specimens, models, and medical instruments.

Veterinary fleam inscribed '1732'. Donated by M.B. Park. Mütter Museum, 17838.32

Despite a move to its current home in the early twentieth century, the display respects the museum’s 19th-century origins and the cases are reminiscent of other cabinet museums of the period. Through its permanent and changing displays, the Mütter Museum aims to foster greater public understanding of the human body and its often-grotesque manifestations, as well as analysing the histories of diagnosis and treatment of disease. Over time, the collection has grown from Mutter’s initial donation of 1,700 teaching objects to the College of Physicians to the impressive figure of approximately 33,000 pieces.

In addition to the shock and awe of some of the permanent exhibits, such as the Soap Lady or the Hyrtl Skull Collection, there are more considered, thought-provoking displays. Broken Bodies, Suffering Spirits questions what it was like to fight, become sick or injured, or take care of the wounded through the prism of the Civil War in Philadelphia. While no battles were fought in or indeed even near the city, many sick or wounded soldiers found their way to local hospitals. A temporary exhibition, on until 16 September 2018, examines the curious 18th- and 19th-century tradition of hair art. Woven Strands presents artworks and jewellery made of human hair from six private collections. These pieces are spectacular in their execution – some forming intricate photograph frames, others beautifully woven bracelets – but the central themes are of love and remembrance.

Scarificator used for wet cupping with blades just below the surface ready to pierce the skin. Mütter Museum, Philadelphia

As with any museum or gallery, the entirety of its collection cannot be exhibited: some pieces are too fragile; some may be duplicate objects, with only the best selected for display. And on a practical level, it would be near to impossible to find the space to display each and every object. I was incredibly fortunate to be shown some of the stored objects by the Collections Manager, Lowell Flanders, which were of particular interest to the Renaissance Skin project. We began with the medical instruments of mostly 19th century origin, but many of the forms were little altered from their earlier incarnations. The majority of tools in the collection are associated with bloodletting performed to rebalance the humours or related to the treatment of pox. Looking at some of these tools with their blades on spring mechanisms, I was warned to keep my hands clear of the openings – I definitely didn’t want to risk breaking my skin while handling anything there! We saw numerous scarificators (see image), a veterinary fleam inscribed with a name and the date ‘1732’ (pictured above), spring lancets, sets of cupping glasses, a bloodletting basin, and a Lebenswecker (literally ‘life-awakener’) once owned by a Dr Lowright. We opened drawer upon drawer of these instruments, indicative of just how ubiquitous they once were within the medical profession.

Human body displaying its internal structure. Mütter Museum, Philadelphia

The tour could have ended here, but Lowell was very generous with his time and thought that no trip to the stores of the Mütter Museum would be complete without seeing the bones and the wet and dry specimens. While this was incredibly fascinating, I couldn’t help but note that you really needed to have a strong constitution to work surrounded by these objects on a daily basis. In the wet specimen room (shelves stacked high with various body parts, including foetuses), the conservator explained his current project to improve the liquid substance that holds the specimens suspended in their jars. At present, the liquid allows for too much movement, which can cause damage in transit. Once the final substance is determined, each wet specimen will be transferred in turn to a new jar. Really, not a job for the faint-hearted. But this served as an important reminder that the role of the museum is not just to educate various audiences through display and research, but also to preserve the objects through a rigorous collections care management programme, only possible through specialist knowledge. In the ‘bones’ room, I was completely struck by a preserved body that showed in all its glory (and gory details) the muscles and structure of the human body (see image).

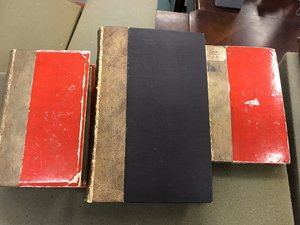

A side trip to the Historical Medical Library and a chance conversation with a member of staff there resulted in the fortuitous handling of five anthropodermic books from their collection, making it the largest collection of anthropodermic bibliopegy in the States. Three of these volumes are bound in the skin of Mary Lynch and, appropriately, are books on female anatomy.

Books bound with the tanned skin of Mary Lynch, 19th century. Historical Medical Library, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia

Lynch was a poor woman in her 20s admitted to an almshouse in Philadelphia in 1868 presenting symptoms of tuberculosis. She contracted intestinal worms from contaminated meat brought to her by her friends and sadly died in January of the following year. Dr John Stockton Hough, who was tasked with performing her autopsy, tanned part of the skin from one of her legs at the same time, using it some 20 years later to bind the three books. Gruesome, yet utterly fascinating, objects such as these make us think carefully about what skin meant to earlier generations. Would Dr Hough’s practice have seemed unscrupulous to contemporaries, or is it just our modern-day sensibilities that make us uncomfortable with such undertakings? While investigating further on books bound with human skin, I came across the term ‘human leather’. Somehow, it didn’t sit comfortably with me to think of my own skin as leather. But why? Perhaps it is because I think of leather as a material to make things, abstracted when removed from its animal origins, or as a commodity to be bought and sold, again without reference to the original body to which it was once attached. Understanding skin and the moral and physical differences between human and animal skin is one concern of the Renaissance Skin project, but it’s always good to confront ourselves with the reality of the concepts we aim to uncover through research.

NAD

With thanks to the staff of the Mütter Museum for allowing me access to their collections and, in particular, Lowell Flanders, Collections Manager and Registrar.

All images copyright of author and published with permission of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.