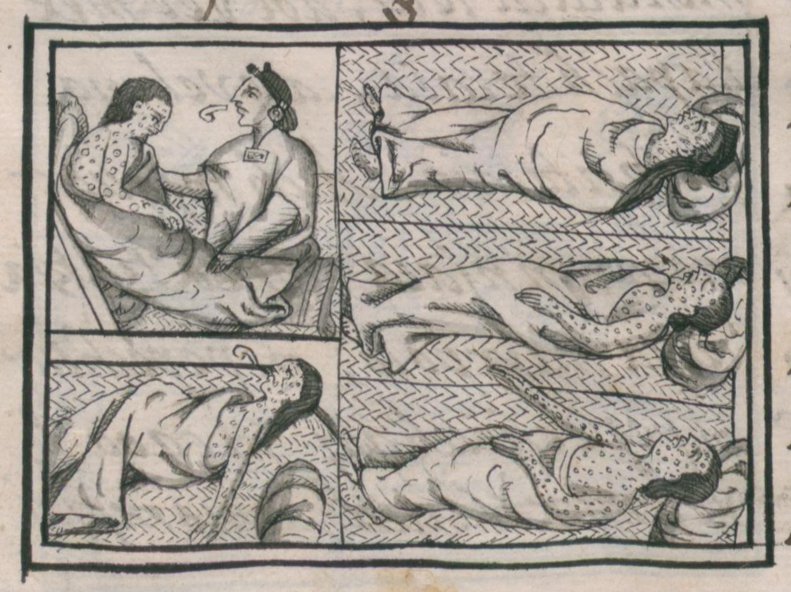

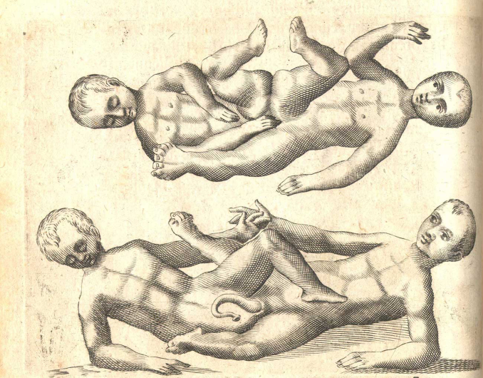

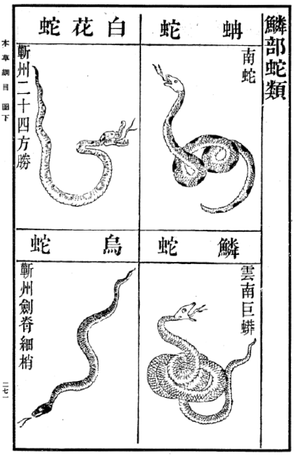

This image is taken from the Florentine Codex, also known as Historia de las Cosas de la Nueva España or The General History of the Things of New Spain, a monumental sixteenth-century work completed under the direction of the Franciscan monk, Fray Bernardino de Sahagún. De Sahagún conducted his research in the Nahuatl language, devising a questionnaire, employing native amanuensis (assistants who would take dictation or copy manuscripts), and spending time with informants in different parts of the country. The illustrations within the manuscript were completed in c.1575 and are attributed to Agustín de la Fuente, a native of Tlatelolco.

The image presented here is the earliest visual record depicting smallpox in the New World. Between 1520 and 1600, smallpox and other European diseases such as measles ravaged the indigenous populations of Mexico and Central and South America. Hundreds of thousands of people died, with some estimates of population loss being up to 90%. The general devastation was noted by contemporaries. In 1634, John Winthrop wrote 'for the natives, they are neere all dead of small Poxe, so as the Lord hath cleared out title to what we possess'.

The link between smallpox and skin transcended linguistic barriers and Galenic theory. The disease was immediately identifiable by the macules - pustules, lesions or boils - it caused on the skin. This image is also particularly remarkable for the careful attention it gives to the progressive nature of the disease and its successive stages. The gradual uncovering of the body in the various panels helps to demonstrate the spread of the pustules, but it also signifies the spiking and dangerous fever for which the disease was well known. While few visual accounts of smallpox survive, those that do display similar attention to the progressive nature of the disease. They remind us that while skin was often the subject of artistic scrutiny, the way in which it signified what was more difficult to represent (in this case delirium, fever, and death) was the cause of its scrutiny.

HM

The Florentine Codex is found in the Medicea Laurenziana Library in Florence.

A digital edition has recently been made available at The World Digital Library.