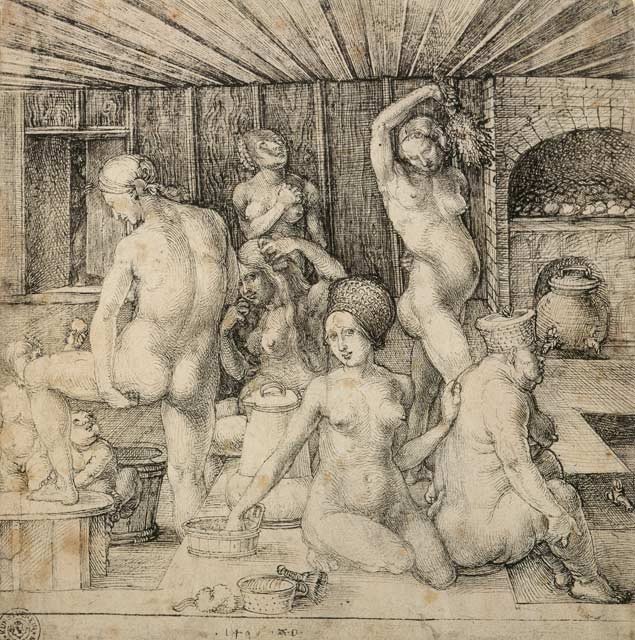

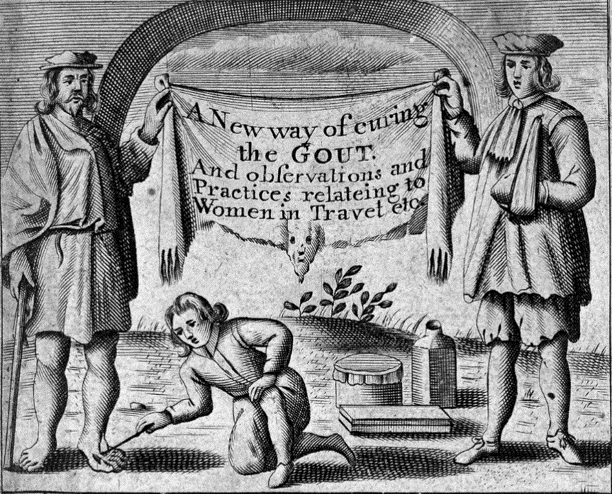

Das Frauenbad or The Women's Bathhouse (1496) by the Nuremberg artist Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) is a pen drawing, probably made as a preparatory study for a print that was never executed. The drawing is a highly technical early demonstration of one-point linear perspective, which Dürer would later go on to outline and explain in Four books on human proportion. Featuring six women from different points of view and in different poses, the drawing essentially models a female body in the round. Its visual insight into the subjects' lives is similarly nuanced, featuring different ages, stages of life, and - concurrently - health concerns.

Baths appeared frequently in works by Dürer and his Nuremberg contemporaries. This is not very surprising, since baths were a feature of German civic life. The earliest record of baths in Nuremberg dates back to 1288, when Konrad von Kuerenburg granted the privilege of a bath from the river Pegnitz to the Franciscan monastery. By the sixteenth century, there were approximately thirteen public baths spread across the city. Although it is not clear which bathhouse is represented here by Dürer, the stove in the background and the tap close to the seated woman in the foreground make it clear that this was a technologically sophisticated bath, distinguishing it from those natural spas with which many medical writers in the sixteenth century were preoccupied.

It is evident from this drawing that Dürer paid close attention to the minutiae of bathing. The bundle of twigs, which serve as the painting's axis of perspective, were a tool for exfoliation. In the Galenic nexus that informed the maintenance of health, baths were not simply about washing, but about carefully managing the process of excretion that skin enabled. For similar reasons, combing your hair (as we see the long-haired woman in the centre doing) was an essential act of cleanliness, while protecting your head against overexposure through the use of of hats and wraps, as worn by the three women at the front of the image, was equally common. Finally, the younger woman bathing her elder reminds the viewer that effective cleansing often required interpersonal attention, a facet of which Nuremberg's civic council were well aware. From 1523, the council paid barber-surgeons to attend to the cupping and bleeding practices demanded by this whole-scale attention to skin. The overt sensuality and intimacy of the drawing, as evidenced by the Peeping Tom in the corner, reminds the viewer simultaneously of the interplay between tactility, eroticism, and health in which skin played a crucial role.

HM

Image: Albrecht Dürer, Das Frauenbad, 1496, inventory number Kl 57. © Kunsthalle Bremen - Der Kunstverein in Bremen, Kupferstichkabinett